Type One Emergence: The example of emergence we have just offered is what might best be identified as Stochastic Emergence. It is all or nothing. At room temperature nothing happens with hydrogen and water. Add the right amount of heat and something radical happens. There is a tipping point that leads to a revolution. We can’t anticipate the new entity. We can only adapt and learn from it. Many share the story of the frog dropped in boiling water—either immediately jumping out to live or being boiled alive very suddenly. Adapt or die might be the calling card of type one emergence.

Type Two Emergence: This type of dynamic change might be defined as Spectrum Emergence. There is gradual change and gradual recognition of this change. There is evolutionary rather than revolutionary change—that is only acknowledged as revolutionary at some later point. Our broken windows scenario exemplifies this second form of emergence. Recognition and acceptance of the change diffuses slowly and often in stages (Rogers, 1995). We can begin to see/anticipate outcomes as the diffusion takes place.

There is the widely told (and somewhat disturbing) example of placing a frog in a slowly warming pot of water. Something remarkable happens (at least hypothetically) when we place a frog in a cool pot of water and slowly heat the water. The frog may not notice the gradual increase in temperature and not achieve the signal to jump for his or her life. As a frog, we must have higher levels of sensitivity to the shifting states. As a sensitive frog we will live, jumping out well before it becomes too late. We will boil to death If we are a stubborn frog who denies the reality of rising temperature. Discernment, feedback sensitivity, and adjustments—rather than reflexive decision-making—dominate our adaptive behaviors with Spectrum Emergence. A bit of distal assessment and slow thinking will also be of great value if we are human beings who confront the challenge of Spectrum Emergence.

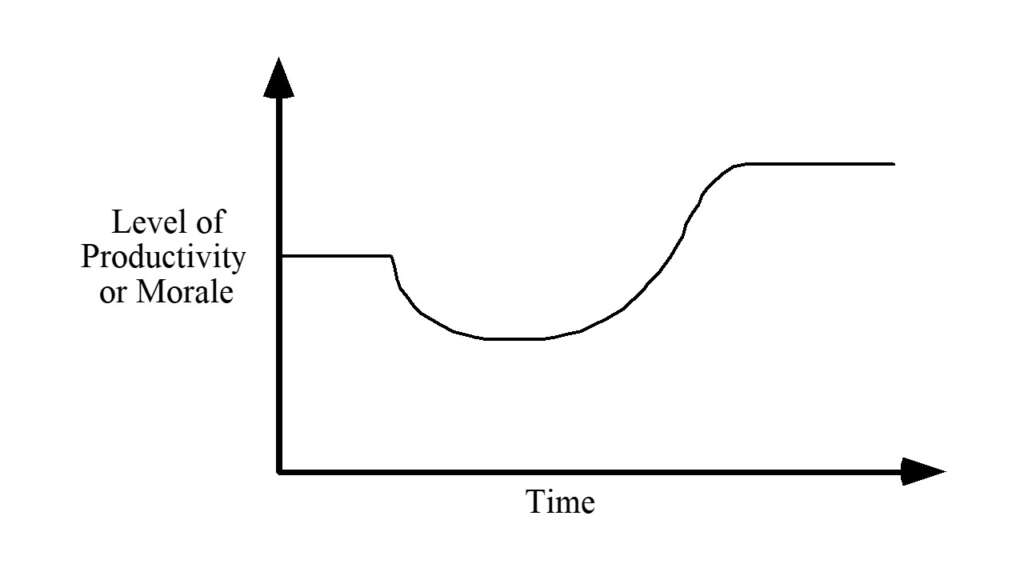

Emergence and the Change Curve: the demand for change is often apparent when facing either a type one or type two emergence. This change might occur “on time” or “too late” (in the case of the stubborn frog). It might be a change that requires major adjustments (revolution) or minor tweaking (evolution). Regardless of the timing or size of the change, it will usually lead to a temporary (perhaps even permanent) reduction in productivity and morale among those facing and engaged in the change (see Graph Three).

As things get “worse” there will be an inclination to go back to the old way (which introduces yet another change and the creation of a new change curve). Alternatively, there is the temptation to try something else (introducing another change curve). Organizations often go through a succession of changes—with each one further reducing productivity and morale (see Graph Three). The process of change itself becomes the major issue. Ralph Stacey (1996) might suggest that the organization has moved beyond the states of complication and complexity to one of Anarchy.

Graph Three: The Change Curve