The Structure and Dynamics of Dreams

Sigmund Freud was very interested in structure and physical locations. He loved the field of archeology and had many archaeological artifacts in his Vienna office. Freud made extensive use of archaeological metaphors in his image of the human psyche. We have layers upon layers of memories and emotions. Psychoanalysts assist their patients in “digging deeper” into their psyche to reveal old relics. I begin the description of dream structures and dynamics by referring back to a critical concept offered by Sigmund Freud, the would-be archeologist.

Freud’s Apparatus

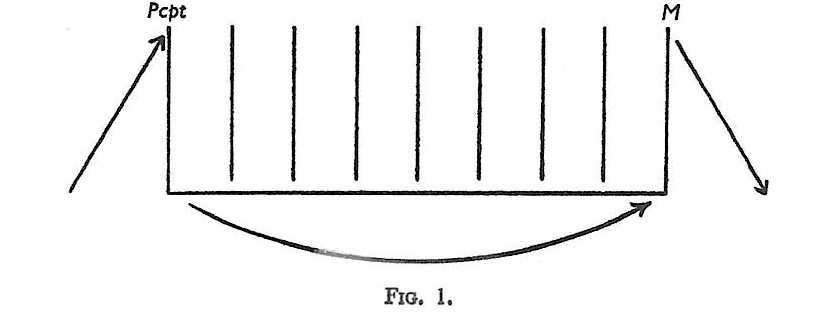

In the middle of his massive and highly influential treatise on dreams, Freud (1900, pp. 536) provides a remarkable framework or apparatus for understanding the structure and dynamics of regression. In many ways, this framework moves well beyond the matter of dreams and dream interpretation. It offers a prescient view of the way in which our mind operates. Freud’s framework is portrayed in spatial form; however, as Freud notes, it actually operates in a temporary manner, with one element of the psychological (Ѱ) system that he describes being activated following another element. It is also important to note that Freud uses abbreviations when describing this framework: (1) perception (Pcpt), (2) memory (Mnem), (3) Motor (M), (4) unconscious (Ucs), and (5) preconscious (Pcs).

We first enter the world of Freud’s apparatus with his observation that the psychic dynamics of this system move in a specific direction (Freud, 1900/1953, p. 537):

“The first thing that strikes us is that this apparatus, compounded of Ѱ-systems, has a sense of direction. All our psychical activity starts from stimuli (whether internal or external) and ends in innervations. Accordingly, we shall ascribe a sensory and a motor end to the apparatus. At the sensory end there lies a system which receives perceptions; at the motor end there lies another, which opens the gateway to motor activity. Psychical processes advance in general from the perceptual end to the motor end. Thus the most general schematic picture of the psychical apparatus may be represented thus (Fig. 1):