Freud (1900/1953, p. 538) now brings in the memory elements of his apparatus and differentiates between those memory elements that are transitory and those that are permanent (it is worth noting that contemporary neuropsychological findings similarly point to memories that are discarded at night and those that are retained and placed in long term storage]:

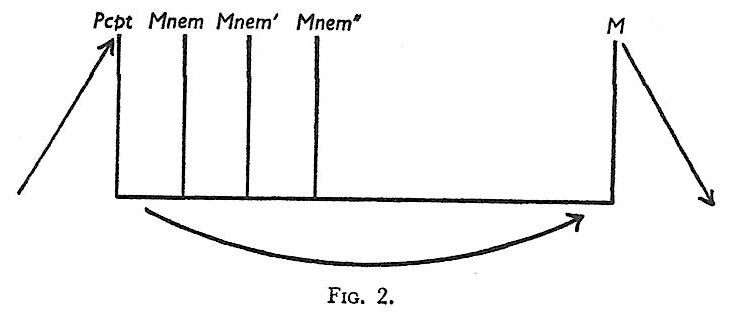

“Next, we have grounds for introducing a first differentiation at the sensory end. A trace is left in our psychical apparatus of the perceptions which impinge upon it. This we may describe as a ‘memory-trace’; and to the function relating to it we give the name of ‘memory’. . . . [T]here are obvious difficulties involved in supposing that one and the same system can accurately retain modifications of its elements and yet remain perpetually open to the reception of fresh occasions for modification. In accordance, therefore . . . we shall distribute these two functions on to different systems. We shall suppose that a system in the very front of the apparatus receives the perceptual stimuli but retains no trace of them and thus has no memory, while behind it there lies a second system which transforms the momentary excitations of the first system into permanent traces. The schematic picture of our psychical apparatus would then be as follows (Fig. 2):

At this point, Freud (1900, pp. 538-539) reminds us that he still lives in a world when memories are linked by association [a concept that has since been replaced by Donald Hebb’s (1949) neurobiological notion that memories (neurons) which “fire together will wire together.” The important point to be noted in what Freud has suggested is that incoming perceptual information is “sticky.” One piece of information will often link with another piece leading to what Jereme Bruner (1973) later identified as the human capacity to “go beyond the information given.” The newly connected pieces of information lead to the construction of a reality that was not portrayed in any one of these pieces.

It is now time for Freud (1900/1953, p. 539) to introduce his first notions about conscious and unconscious processes as they pertain to our perceptual and memory systems:

“It is the Pcpt. system, which is without the capacity to retain modifications and is thus without memory, that provides our consciousness with the whole multiplicity of sensory qualities. On the other hand, our memories—not excepting those which are most deeply stamped on our minds—are in themselves unconscious. They can be made conscious; but there can be no doubt that they can produce all their effects while in an unconscious condition. What we describe as our ‘character’ is based on the memory-traces of our impressions; and, moreover, the impressions which have had the greatest effect on us—those of our earliest youth—are precisely the ones which scarcely ever become conscious. But if memories become conscious once more, they exhibit no sensory quality or a very slight one in comparison with perceptions.”