Following the war, the United States government tried to forcibly remove all the Ojibwe to Minnesota, west of the Mississippi River. The Ojibwe resisted, and there were violent confrontations. In the Sandy Lake Tragedy, several hundred Ojibwe died because of the federal government’s failure to deliver fall annuity payments. The government attempted to do this in the Keweenaw Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Through the efforts of Chief Buffalo and the rise of popular opinion in the U.S. against Ojibwe removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to reservations on ceded territory.

In Canada, many of the land cession treaties the British made with the Ojibwe provided for their rights for continued hunting, fishing and gathering of natural resources after land sales. The government signed numbered treaties in northwestern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. British Columbia had not signed treaties until the late 20th century, and most areas have no treaties yet. The government and First Nations are continuing to negotiate treaty land entitlements and settlements.

Culture

The Ojibwe have traditionally organized themselves into groups known as bands. Most Ojibwe, except for the Great Plains bands, have historically lived a settled (as opposed to nomadic) lifestyle, relying on fishing and hunting to supplement the cultivation of numerous varieties of maize and squash, and the harvesting of manoomin (wild rice) for food. Historically their typical dwelling has been the wiigiwaam (wigwam), built either as a waginogaan (domed-lodge) or as a nasawa’ogaan (pointed-lodge), made of birch bark, juniper bark and willow saplings. In the contemporary era, most of the people live in modern housing, but traditional structures are still used for special sites and events.

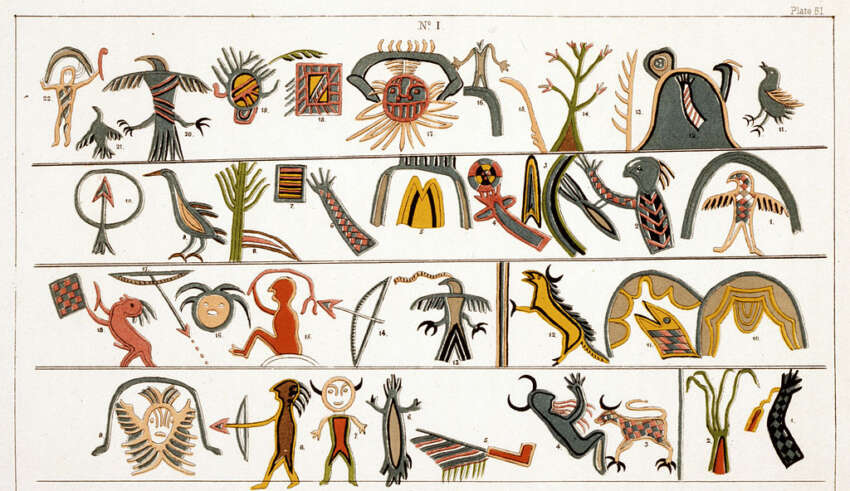

They have a culturally specific form of pictorial writing, used in the religious rites of the Midewiwin and recorded on birch bark scrolls and possibly on rock. The many complex pictures on the sacred scrolls communicate much historical, geometrical, and mathematical knowledge, as well as images from their spiritual pantheon. The use of petroforms, petroglyphs, and pictographs has been common throughout the Ojibwe traditional territories. Petroforms and medicine wheels have been used to teach important spiritual concepts, record astronomical events, and to use as a mnemonic device for certain stories and beliefs. The script is still in use, among traditional people as well as among youth on social media.

Some ceremonies use the miigis shell (cowry shell), which is found naturally in distant coastal areas. Their use of such shells demonstrates there is a vast, longstanding trade network across the continent. The use and trade of copper across the continent has also been proof of a large trading network that took place for thousands of years, as far back as the Hopewell tradition. Certain types of rock used for spear and arrow heads have also been traded over large distances precontact. During the summer months, the people attend jiingotamog for the spiritual and niimi’idimaa for a social gathering (powwows) at various reservations in the Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting wild rice, picking berries, hunting, making medicines, and making maple sugar.