There is a partial answer to this perplexing (and paradoxical) problem of powerlessness. We can serve as a Sleep Scientist, which allows us to experience our own “agency”. We can do something about our inability to fall asleep. As a result, we can remain optimistic about getting a good night of sleep. A powerful, paradoxical dynamic is in operation: to worry about the inability to fall asleep actually increases the chance that we will find it difficult to fall asleep. To not worry about sleep is to increase the change that sleep will take place. This exemplifies a self-fulfilling prophecy—a positive feedback loop that enables one positive outcome to produce another positive income and, in return, a further increase in the possibility that the first outcome will reoccur and often amplify.

There is another paradox that accompanies and can complement our attempt to fall asleep. This paradox operates in a manner that mirrors a strong desire to remain awake. This paradox concerns our desire to stay awake. We are reading a book. This according to our sleep survey results becomes a great way to fall asleep! We might be watching a wonderful movie or an exciting sporting event. We are trying to stay awake in order to monitor our teenager’s return home after an evening of dancing (and probably “making out” with their date). What happens? We fall asleep. The harder we try to remain awake, the pull toward “dosing off” gets stronger and stronger.

We might give up (unless we are trying to be a diligent parent). We reluctantly turn off the movie, decide to record the sporting event, and head off to bed. What happens. We can’t fall asleep in bed. We once again curse the God of Night. This d*%*^&&* God is a jokester who is messing with my mind, body and sleep. Much as in the case of the person who can’t fall asleep because they try too hard, the paradoxical nonsleeper can only sleep then they do not want to sleep.

All of this means that we sometime can fall asleep by trying to stay awake. We see this with children. Just tell a child that you will give them a quarter (or perhaps a dollar given inflation) if they can stay awake for the next half hour and they will be asleep in ten minutes. We don’t know all of the neurobiology that creates these paradoxical conditions, but do know that they exist—so as Sleep Scientists we can make use of these paradoxes to get a quality night of sleep.

Cluster Two: Temperature, Sights and Sounds

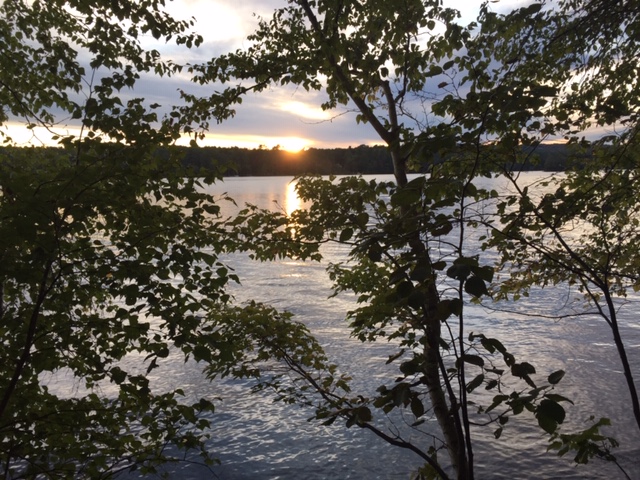

We human beings are creatures of our environment. Our sleep cycle is dictated in part by our circadian rhythm—which, in turn, is strongly influenced by the appearance and disappearance of the sun. There is no reason to believe that light and dark in our bedroom similarly influences our pattern of sleep. Apparently, light influences our sleep even when our eyes are closed. Closely related to the presence or absence of the sun is the heating and cooling of the environment in which we live. Once again, we are often influenced by the temperature of the room in which we are sleeping.

A third factor is also influenced (at least indirectly) by the sun. This is the presence or absence of sound. Human beings tend to be less active (in most societies) when the sun goes down, leading to less noise and more moments of silence. While the presence of electricity and 2-hour media has made silence more elusive, there is still the opportunity for finding some level of quiet when we are going to sleep.