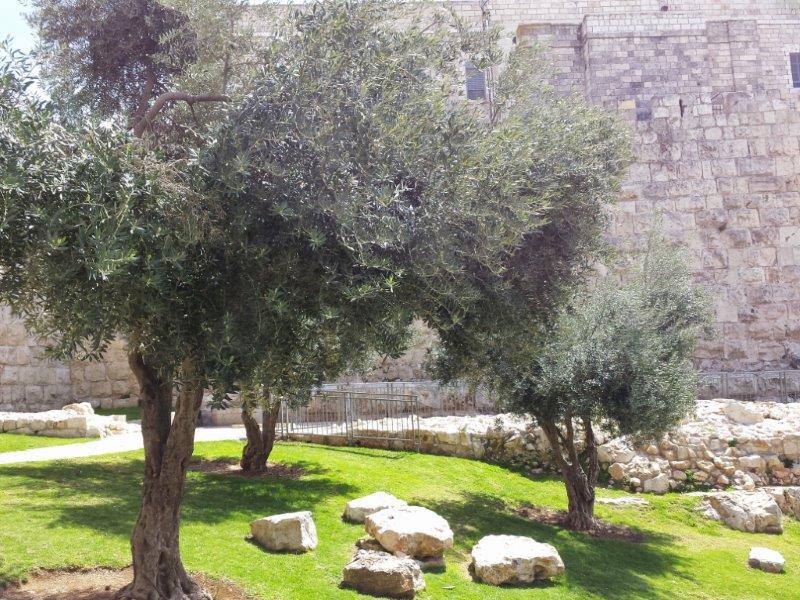

Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs

Friendships are influenced by their political context, which in this study is a situation of oppression by the Israeli authorities of Palestinians. Oppression occurs within Israel, but much more in the Palestinian Authority. Most of the Israeli towns and villages are either Jewish or Arab, but there are some mixed towns. One study found that Jews and Arabs living door to door in the town of Acre had positive relationships, but retained some social distance and no acculturation between the two groups took place (Deutsch, 1985). This was in the early eighties. Since then times have changed. There was a first and a second Intifada, and tension between Jews and Arabs rose. Arabs and Jews within Israel are deeply divided and live segregated lives. Their relations seem to have worsened since 1995 and have become more violent (Smooha, 2011). Furthermore, stigmatization and racism became part of the public discourse in Israel and normative among Jews versus Palestinians (Herzog et al., 2008; Mizrachi & Herzog, 2011; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2004).

One major obstacle in the relationships between Jews and Palestinians is the mutual lack of trust. “Jewish Israelis tend to regard Palestinian Arabs, including those who are citizens of the state of Israel, as threatening and malicious” (Rabinowitz, 1992, p. 517). This threat may be perceived as one or more of the following: a permanent existential threat, the realistic threat from Palestinians, the threat to Jewish hegemony in the State of Israel, and/or the threat to the moral worth of the Jews’ national identity (Sonnenschein et al., 2010). The Palestinian-Israeli conflict, originally a native-settler conflict, was described as one of the most durable and intractable conflicts since World War II (Mi’Ari, 1999). Apart from the realistic aspects of the conflict, also unconscious processes resulting from socio-political trauma seem to keep the different sides of the conflict apart (Brenner, 2009; Shalit, 1994; Weinberg & Weishut, 2011). Not surprisingly, friendships between Jewish Israelis and Arabs were described as particularly complicated and vulnerable (Baum, 2010), and even as “befriending the enemy” (Joubran & Schwartz, 2007).

Another obstacle in relationships between Israelis and Palestinians, albeit smaller, is the issue of language of communication. Hebrew is the dominant language in all domains of life in Israel. For Israeli Palestinians, Hebrew is a second language that is compulsory in the school curriculum. Lack of fluency in Hebrew makes it for Palestinians difficult to function effectively outside Palestinian towns and villages (Amara, 2007). By contrast, in the Palestinian Authority the dominant language is Arabic and Hebrew is not a compulsory language. For Palestinians, whether living in Israel or in the Palestinian Authority, working in Israel and learning Hebrew may be a form of empowerment, whereas resistance to speaking Hebrew may be a form of resistance to Israeli oppression (cf. Rahman, 2001).