Archetypes and Mythic Figures

The third interpretation, coming from the world of Jungian Psychoanalysis, concerns both the Ego and Id (or more accurately Jung’s unconscious life). During the first years of the 20th Century, Carl Jung proposed that there are two ways in which we think. There is directed thought that is based on logic and verbal discourse. Jung sees this form of thought as most directly manifest in science and considers directed thought to be dominant in contemporary Western societies. The second form of thought is defined by Jung as fantasy based. It is a passive enterprise with strong inclinations toward association and imagination. Fantasy thought is founded in mythology and has been dominant in most societies (other than those now dominated by science) since the beginning of human history.

It is this latter form of thought that occupies most of Carl Jung’s work and is spectacularly on display in Jung’s Red Book (an absolutely unique volume that was published many years after it was written by Jung and was kept locked up away from public view). This large book contains not only beautiful and often compelling images painted by Jung but also remarkable handwritten Gothic text through which Jung offered his accompanying narrative. I know of no other published document that conveys such a strong and convincing argument for the power and importance of visual images. The mythic world is truly alive and well in the Red Book world created by Carl Jung.

This mythic world is also alive and well in the movies and television shows that prevail in our collective life. Joseph Campbell’s description of mythic characters and themes have clearly influenced the stories told by George Lucas in the Star Wars movies—as have other renderings of ancient myths been captured in the content of many superheroes portrayed in 21st Century movies. Do not the fantasy movies of the 21st Century provide concrete evidence of the impact which media moguls believe that mythic, caped and masked characters have on imagination and decision to go to see an action-packed movie on a big screen?

Once again, does the concrete, tangible telling of a mythic tale on a television set in our home or on a screen at a neighborhood movie theater make this tale even more likely to show up in our dreams? Some critics suggest that our own personal myth-making capacity is blunted by its enactment on the screen. If this is the case, then are we likely to borrow these media-created myths when generating our dreams—rather than create our own mythic figures and stories? Does Peter confiscate Elizabeth Taylor and Robert Redford rather than fashion his own protagonists based on people he knows or uniquely fabricates?

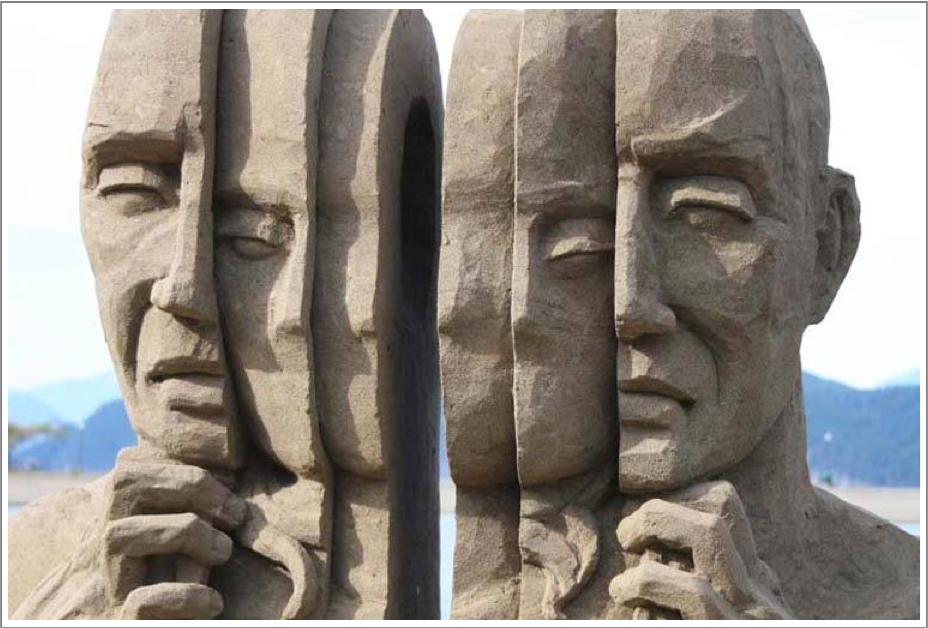

Images and Dreams

This emphasis on visual images as direct and compelling conveyors of mythic narratives and narratives is relevant to our exploration of dreams—for virtually all dreams are intensely visual (other than some dreams that tend to occur early in a night of sleep). When looking at the images provided by Jung in the Red Book or George Lucas in the Star Wars productions, one can’t help but be struck by similarities to be found between these images and the images that may have appeared in one’s own dreams.

This is not surprising given that many of Jung’s images come from his own dreams and Lucas’ images come from the study of collective myths. What makes Jung remarkable is his capacity to not only recall these images but also portray them in his drawings and painting (much as some writers can recall and capture the content of their own dreams in their novels and plays). What makes Lucas remarkable is his capacity to translate the oral and written myths of ancient times into contemporary visual experiences.