Epistemological Foundation of The Edge of Knowledge

The final belief is to believe in a fiction, which you know to be a fiction, there being nothing else. The exquisite truth is to know that it is a fiction and that you believe in it willingly. — Wallace Stevens

What an extraordinary statement. It seems to shatter all of our firm convictions that there is truth in the world and that what we should believe is based in a clear sense of truth and reality. But is this really the case? Is Stevens telling us something that rings true, especially as we enter the third decade of the 20th Century. We would suggest that our own field, psychology is one of the “fictions” of which Stevens speaks. It is a fiction which can be of great value to society if used in a wise and skillful manner and if used with full knowledge that it is only one of many fictions that help inform the complex human condition.

The Constructivist Foundation

The Edge of Knowledge is founded on a constructive foundation–with recognition that any psychological “findings” must be set in a specific context and must always be considered “fictions” in the sense offered by Stevens. The following essay conveys the essential points to be made regarding this constructivist foundation:

Psychology and the Social Construction of Reality

With this base in a social constructive perspective on psychology, we will be producing essays in this journal that purport not to be telling the “truth” but rather to be exploring diverse perspective and practices in the field of professional psychology. This will allow us to remain on the edge of knowledge in this field–but then what is the edge of knowledge really all about?

What is at the Edge of Knowledge?

To provide a broader sense regarding the mission and vision of The Edge of Knowledge, we provide the following more general statement regarding this epistemological edge. In setting up this broader perspective, we offer a basic question: what is at the edge of knowledge? To answer this question, we need to mix together a bit of epistemological theory and the “wisdom” offered by an American administrator, Donald Rumsfeld. While Rumsfeld might be criticized for many other things, he does seem to be quite wise about the nature of knowledge (epistemology).

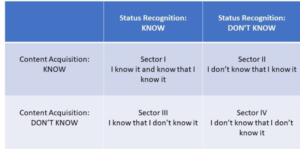

He noted that there are four conditions with regard to knowledge: (1) there are some things we know and we know that we know it, (2) there are some things that we know and don’t realize that we know it, (3) there are some things that we don’t know and know that we don’t know it, and (4) there are some things we don’t know and don’t know that we don’t know it. We can diagram these four conditions by creating one dimension concerning the acquisition of specific content (direct knowledge), and a second dimension concerning our level of awareness regarding the status of our knowledge.

The Edge of Knowledge is embedded in the recognition that all knowledge resides near some edge – the last four letters of the word “knowlEDGE” even convey this important fact.

The Edge of Knowledge is embedded in the recognition that all knowledge resides near some edge – the last four letters of the word “knowlEDGE” even convey this important fact.

At a more precise level, we suggest that the edge of knowledge is particularly prevalent in Sector III (I know that I don’t know it) – which is the primary source of motivation to learn more (to become knowledgeable about something). Sector II is also an important element of the edge—it involves a process of appreciation (recognizing that we know more than we are initially aware). There is even a strong “edginess” to be found in Sector IV – as we become aware that there are areas in which we are not knowledgeable but should be.