Arthur C. Sandstrom

I awoke to the ringing of the phone a few minutes after 2:00 a.m. Not the annoying electronic warble of today’s instruments, but the honest, old-fashioned clapper jangling, like a Big Ben alarm clock, going off. I groaned and peered out of the window, seeing nothing but bright sunshine and blue sky. The weather in Nome, Alaska, was normally like this in August although brief snow squalls had occasionally made appearances. I fumbled the handset to my ear. “Unhhh?”

“Art? You awake?”

I recognized the voice. For an instant I was tempted to tell my boss that, no, I was asleep and just dreaming that he was calling me. Better judgment prevailed. “Mmmph… yeah. What’s up?”

“Sorry to wake you, but I just got a call from the night shift supervisor in Anchorage. The captain of the North Wind radioed Adak, who called Anchorage. There’s some kind of emergency and they need to talk with someone here right away. They want to come up on CW, though…”

Being the station’s chief operator as well as primary CW (continuous wave, or International Morse Code) operator, I didn’t need to hear any more.

“Okay. I’ll go down and see if I can raise her.”

“Thanks… and call me if you need any help.”

“Right.” I hung up, knowing he offered that to sop his conscience for interrupting my sleep. I didn’t tell him that I had come crawling home that Saturday morning from one of the local bars only an hour before.

* * *

I went downtown, opened the station and headed for the radio room. I sat down at the console, yawned, fired up the remotely-controlled transmitter and receiver and tuned them to the international calling and distress frequency of 500 kilocycles.

Stroking the paddles on my Vibroplex® key, I sent NRFJ DE ALC22 K (Coast Guard Cutter NRFJ, this is Nome). I wondered why the cutter North Wind, which had been operating around Point Hope and reporting herself yesterday as heading for Juneau, wanted to talk to someone in Nome at this hour.

Almost immediately came the response: DE NRFJ QSW/QSY IMI K (This is North Wind. What frequencies? Over).

I told the cutter’s operator to tune to 472 kilocycles working frequency both ways. After recontact, the details of the situation, spelled out in hurriedly-sent dots and dashes rattling into my headphones, made itself clear.

Someone on board was showing symptoms of a heart attack, and the ship was en route to Nome, the nearest town with a hospital. The cutter had no medical doctor on board and the situation was beyond its corpsman’s abilities. The captain requested that I have Nome’s doctor standing by when the ship arrived in the roadstead in an estimated two hours. I was also requested to make sure only the doctor and medical staff knew of this.

Funny, I thought. Why the secrecy over a medical emergency? Wasn’t Anchorage told what it was about? And, come to think of it, Coast Guard crews were usually in good physical shape and too young to have heart attacks…

After confirming and clearing contact with the ship, I sat back and wondered how Doc would react to my call at this hour (now close to 3:00 a.m.) requesting that he come down to the harbor and receive a heart attack patient. Oh, well…

* * *

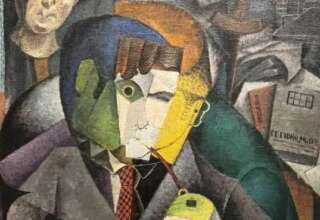

Doc and I stood on the quay watching North Wind’s gig maneuver carefully alongside. To my surprise, the ship’s captain was among the handful in the boat. More to my surprise, the patient being carefully lifted out on a stretcher was a tall, older man with salt-and-pepper hair and bushy eyebrows. He had craggy features, a prominent nose, and was dressed in civilian clothes. After the cutter’s captain quickly introduced himself to Doc, the patient, who had kept his eyes and mouth closed, was placed in the hospital’s carryall, which served as ambulance. He and Doc, accompanied by the captain, were rushed off to the hospital. I was left standing alone with the gig’s crew, none of whom showing any inclination to chat. The quiet morning held no other interests to me. Still sleepy and bored with staring at the North Wind at anchor a half mile out, I eventually made my way back home. After calling my boss (gleefully knowing that I woke him) and reporting the events, I went back to bed.

* * *

The labyrinthine world of governmental cloak and dagger activities loves its subterfuge and it is excruciatingly slow to divulge its activities. Suffice it to say, though, that during that time frame a certain project was underway in the Cape Thompson area, a little north of Point Hope. That project, called “Plowshare,” included plans to detonate a nuclear device in hopes of creating an instant harbor, and some fairly important folks with the Atomic Energy Commission were closely involved.

Doc saw his patient through the “heart attack,” which turned out to be a false alarm, and I eventually received a thank you from the Coast Guard for my assistance. Only afterwards did I tumble to the patient’s identity. Several years later at a reception in Nome, I again saw the “patient.” This time we were formally introduced and I shook hands with that tall gentleman with the bushy eyebrows, Dr. Edward Teller, the ‘father of the hydrogen bomb.’